# The Visionary Woman Who Foretold Climate Change in the 19th Century

Written on

Chapter 1: The Pioneering Research of Eunice Foote

In 1856, Eunice Foote made a groundbreaking scientific discovery that would later be recognized as pivotal in understanding climate change.

Today, the implications of greenhouse gases are well-known. The combustion of fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide and sometimes methane, contributing to the greenhouse effect that traps solar heat. This process leads to global warming and the resulting climate anomalies we face today.

Since the 1980s, many have been aware of these issues, especially after James Hansen's testimony to Congress. At that time, I was just 20, grappling with a sense of foreboding as I absorbed the information. I couldn't help but think: If only we had recognized this sooner!

Interestingly, the foundational concept of greenhouse gases had already been discovered over a century earlier by Foote, a female suffragette, who conducted innovative experiments in 1856. Her work included a prophetic prediction about the potential for future global warming.

Foote was born in 1819 on a Connecticut farm and raised in Bloomfield, New York. Unlike many women of her time, she was fortunate enough to receive a robust education, thanks to her parents who enrolled her in the Troy Female Seminary, where she excelled in advanced mathematics and science. Additionally, she was a strong advocate for women's rights, serving on the editorial board of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Her scientific curiosity was fueled by contemporary debates in geology, which were revealing significant climate shifts throughout Earth's history. Scientists were analyzing coal deposits from ancient swampy seas and deduced that the atmosphere had, at various times, contained much higher concentrations of carbon dioxide. However, as noted by geologist Joseph D. Ortiz, the scientists of the Victorian era did not connect increased CO2 levels to temperature changes.

Foote was intrigued by the concept of whether gases could retain heat, and if so, which ones were most effective.

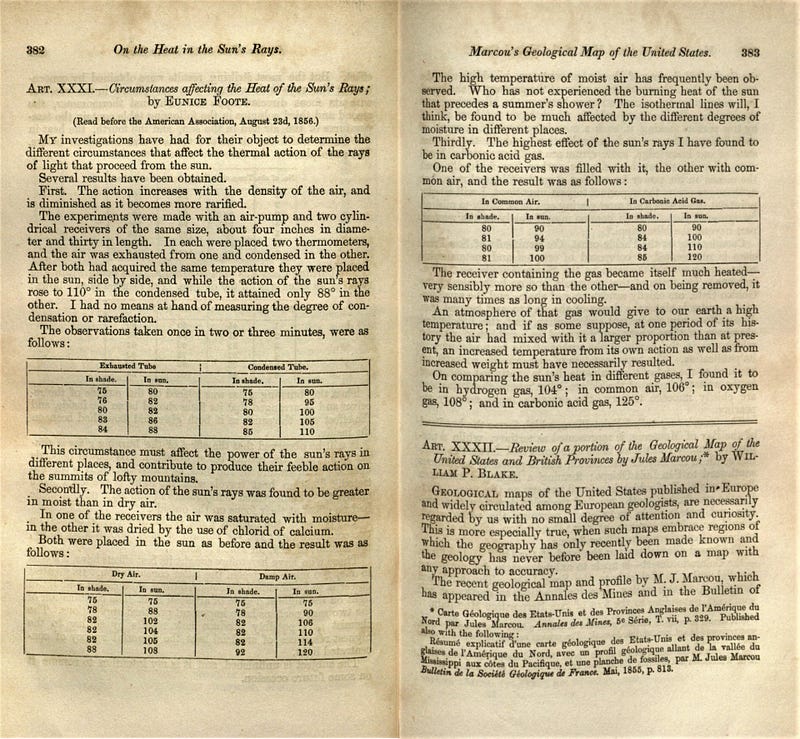

She devised an innovative experiment, using glass cylinders filled with various gas mixtures—thin air, denser air, humid air, and carbonic acid (now known as CO2). After exposing them to sunlight and then shade, she measured the internal temperatures with thermometers to analyze how each gas affected heat retention.

Foote made several significant observations. She found that thinner air was less capable of trapping heat, explaining why mountaintops tend to be colder than sea level—something that had puzzled scientists of her time. Instead of attributing it solely to the angle of sunlight, her findings indicated that the less dense air at higher altitudes held less heat.

Her most striking discovery was that the cylinder filled with CO2 heated up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit in sunlight, a full 20 degrees warmer than the one containing regular air. Furthermore, it retained heat for a longer duration.

Her original paper is a concise and clear account of her findings. In the closing remarks, Foote reflected on how elevated CO2 levels could lead to higher temperatures on Earth:

"An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature from its own action as well as from its own weight must have necessarily resulted."

This single, impactful statement captured the essence of greenhouse gases and their global implications. Foote's insights were not only relevant to the past but also provided a chilling glimpse into the future.

When Ortiz discovered Foote's paper a decade ago, he remarked on the elegance of her research, noting, "She took what was known from geology, infused it with physical experimentation and helped to create the modern field of climate science."

Unfortunately, it took a long time for Foote to receive recognition for her groundbreaking work. Although her findings were published in the American Journal of Science and Arts in November 1856, she was unable to present her research at the scientific conference that year. Instead, her husband spoke on his own experiments, and Foote's significant contributions were overshadowed.

Years later, the renowned scientist John Tyndall replicated Foote's experiments and received accolades for demonstrating the greenhouse effect, inadvertently overshadowing Foote's earlier work. It’s unlikely he had access to her research, as communication in the 19th century was limited, leading to simultaneous discoveries without awareness of one another.

Foote's contributions remained largely forgotten until 2011, when retired geologist Raymond Sorensen stumbled upon a report discussing her presentation. This sparked a reevaluation of her role in climate science, leading to increased recognition in academic circles.

Reflecting on this history, it's sobering to realize that the risks associated with greenhouse gases were understood 150 years ago. If society had acted sooner, we might have been able to transition our energy production more gradually.

However, the complexities of understanding the rapid increase in CO2 emissions and the interconnected challenges posed by climate change were not fully recognized at the time. Many scientists believed that warming might enhance agricultural productivity, leading to a mixed legacy of hope and concern.

Nonetheless, it's remarkable to acknowledge that Foote foresaw global warming long before it became a pressing concern.

The first video, "Three Pioneers Who Predicted Climate Change," dives into the lives of early thinkers who laid the groundwork for our understanding of climate science.

The second video, "How to Think About Climate Change," features William Happer discussing the complexities of climate science and its implications.

This exploration of Eunice Foote's legacy serves as a reminder of the importance of recognizing contributions from diverse voices in science.