A Trailblazer in Chemistry: Elizabeth Fulhame's Legacy

Written on

Chapter 1: The Early Life of Elizabeth Fulhame

The widely accepted narrative credits Swedish chemist Jöns Jakob Berzelius with the discovery of chemical catalysis in 1835. He characterized it as “the property of exerting on other bodies an action which is very different from chemical affinity, producing decomposition in bodies and forming new compounds without being part of them.” This foundational concept has solidified Berzelius's status as a key figure in chemistry. However, it is often overlooked that Scottish chemist Elizabeth Fulhame published findings on catalysis over 40 years earlier.

Details regarding Elizabeth's life prior to adulthood remain scarce. She resided in Edinburgh with her Irish husband, Dr. Thomas Fulhame, who specialized in treating postpartum infections at the University of Edinburgh. It is likely that Elizabeth's connections through Thomas allowed her access to prominent scientific thinkers of her time. As Thomas was enrolled in a chemistry course, Elizabeth may have utilized his textbooks for her studies.

In 1780, Elizabeth found herself with ample free time and decided to experiment with infusing cloth with metals like gold and silver through chemical processes. She began by soaking silk threads in nitrate of gold or other metal salts and then exposing them to light. When she shared her ambitious project with her husband and friends, they dismissed her efforts as “improbable.” This skepticism only fueled her determination, leading her to conduct experiments that eventually yielded promising results.

“Despite considerable effort, I initially doubted the significance of my small gold and silver cloth samples; however, perseverance led me to create larger pieces,” she later reflected.

Fulhame's innovative photochemical imaging technique on cloth was groundbreaking. Recognizing its potential applications, she proposed that maps could be enhanced using her method, stating: “This invention can be applied to painting and improve geography studies. I depicted rivers in silver and cities in gold, resulting in a visually appealing effect that alleviates the struggle to trace rivers' paths.”

Though she may seem like a mere amateur scientist or an alchemist chasing quick profit, Elizabeth was actually well-versed in the contemporary scientific theories of her time.

Section 1.1: A Meeting with Joseph Priestley

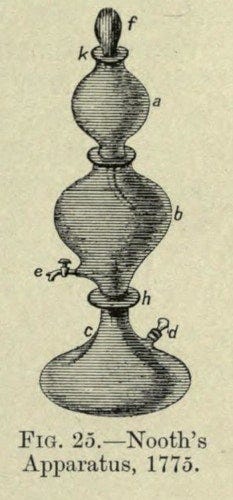

In 1793, Elizabeth had the opportunity to meet chemist Joseph Priestley in London. She showcased her dyed fabrics and shared her observations with him. Priestley was impressed and encouraged her to publish her findings. Known for discovering carbonated water and possibly oxygen, Priestley faced his own challenges as he was exiled from England the following year due to his controversial political views.

In November 1794, Fulhame published a comprehensive account of nearly 15 years of her chemical research in her book titled An Essay on Combustion, with a View to a New Art of Dying and Painting, wherein the Phlogistic and Antiphlogistic Hypotheses are Proved Erroneous. In the introduction, she critiqued the theories of six notable chemists, clearly articulating her disagreements.

Her central thesis posited that only the hydrogen in water could restore oxygenated substances to a combustible state. She argued that water was the sole source of oxygen capable of oxygenating combustible materials. In contrast, Priestley and his contemporaries claimed that oxygen still contained water.

Elizabeth's significant contribution was her discovery that combustible substances like hydrogen and charcoal could reduce metals at room temperature, a process previously thought only possible at high temperatures in furnaces. She also became one of the first to discuss the dynamic aspects of oxidation and reduction, noting that some reduced metals vanished when exposed to air.

“Finding that existing theories could not explain my experiments, I formed my own opinions, regardless of the authority of renowned figures like M. Lavoisier. I believe that every theory must stand on its own merits,” she expressed. Her insights into combustion revealed how nature maintains equilibrium through the consistent recycling of air and water.

Though her book garnered attention, not all responses were positive. Male scientists were particularly resistant to her criticisms of established theories. Priestley himself dismissed her ideas as “fanciful and fabulous.”

Section 1.2: The Impact of Fulhame's Work

Elizabeth anticipated backlash, as she noted in her introduction: “Criticism is inevitable; some are so unaware that they become defensive at any hint of learning, particularly when that learning comes from a woman. Others fancy themselves dictators in science and react with anger when their perspectives are challenged.”

Despite the criticism, her work received acknowledgment. Count Rumford referred to her as “ingenious and lively,” and her findings sparked widespread discussion. A 1798 review of her book in the medical journal Annales de Chimie spanned 28 pages and was one of several French reviews; a German translation also surfaced that year.

When her book was published in America in 1810, Elizabeth was recognized as a corresponding member of the Chemical Society of Philadelphia. The Society noted that her contributions to chemistry could no longer be dismissed based on gender. An advertisement accompanying the American edition critiqued the scientific establishment for its sexism, stating: “The insightful work of Mrs. Fulhame deserves far more attention than it has received... Even if it is uncomfortable for some to accept a woman challenging established scientific beliefs, her insights undeniably present significant obstacles to long-held views.”

Although some of her experimental methods may seem outdated, they have allowed for consistent replication by modern scientists. While some approaches were deemed “flawed,” her insights were considered remarkably advanced for her time. Although she did not directly discover photography, her work laid the foundation for its chemical processes, occurring 50 years before Daguerre's innovations.

Elizabeth Fulhame exemplifies the remarkable achievements of determined women in science, advocating for women's rightful place in the scientific community.

Chapter 2: Recognizing Fulhame's Contributions

The first video titled "What does it mean to be a catalyst for change?" delves into the essence of catalysis and its broader implications in scientific progress.

The second video, "Being a Catalyst for Change 03 14 2024," explores the ongoing influence of individuals like Fulhame in driving scientific advancements and inspiring future generations.