The Silent Collapse of Our Food System and Its Impacts

Written on

Chapter 1: The Shrinking Chessboard

The landscape we rely on for sustenance is rapidly diminishing, exacerbating the effects of climate change. Why do we prioritize vehicles over food production?

Created by author

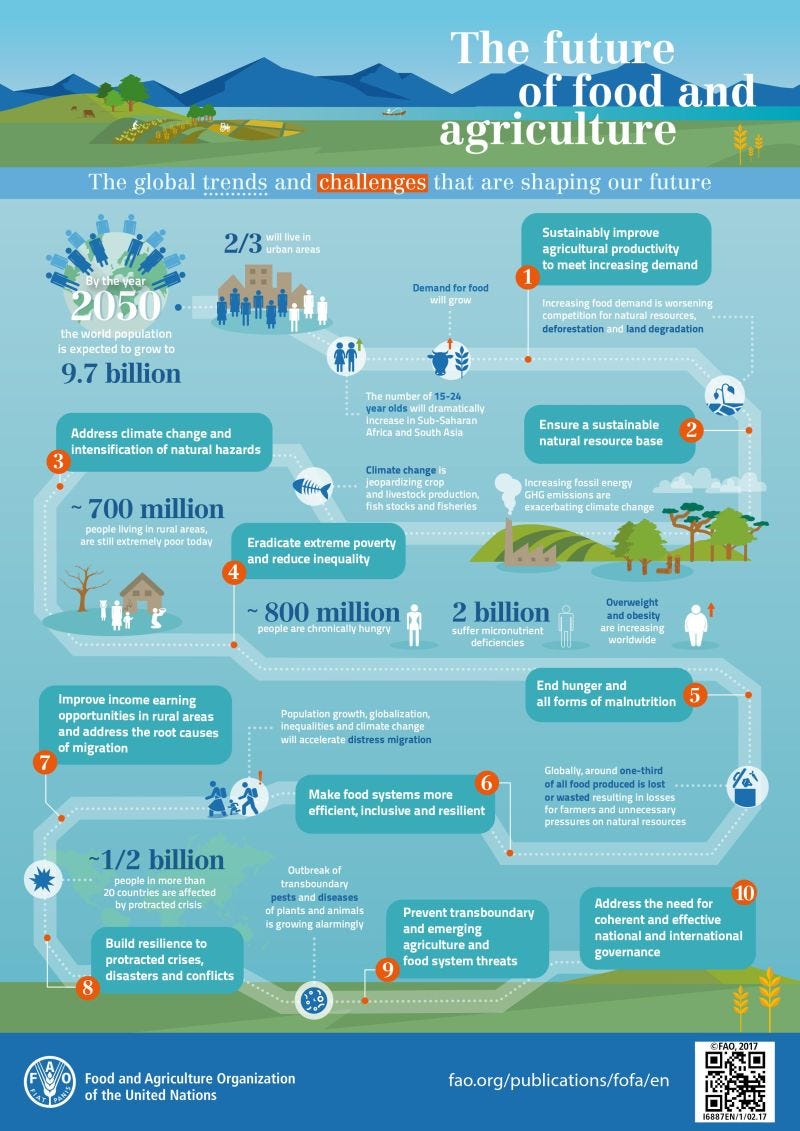

A recent United Nations report highlights that human actions are the leading cause of the most pressing existential threats we face. While climate change and biodiversity loss are widely recognized, another critical issue—land degradation or desertification—often goes unnoticed. Our planet is losing arable land at an alarming pace due to self-inflicted factors like over-farming, excessive livestock grazing, rampant construction, and climate change itself. This crisis goes beyond mere soil loss; it escalates food and water insecurity and increases greenhouse gas emissions. Unfortunately, it fails to receive the attention it deserves.

Since the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the UN has hosted three conventions to address climate change, biodiversity, and desertification. The climate convention often steals the spotlight during its annual COP summits, such as the recent COP28 in Dubai. In contrast, the biodiversity and desertification conventions host their summits biannually, yet they attract little interest.

Many mistakenly see 'desertification' as a problem confined to arid regions, but it fundamentally concerns land degradation. Ironically, in a capital-driven society dominated by social media, our land is deteriorating due to branding issues, while the struggle against land degradation faces a universal challenge: our need for food. Approximately 40% of the Earth's land, totaling around 5 billion hectares, is utilized for agriculture. Of this area, one-third is allocated for crop production, with the remainder for livestock grazing.

The Silent Soil Crisis

Climate models often overlook a vital component: soil degradation. Soil serves as a massive carbon reservoir, holding about 80% of the planet's carbon. When drought occurs, it releases greenhouse gases. Over the past five centuries, human activities—particularly agriculture—have led to the depletion of nearly 2 billion hectares of land, an area larger than Russia. This exploitation has emitted approximately 500 billion tons of CO2 equivalent, accounting for a quarter of today's global warming. If this trend persists, we could see an additional 120 billion tons of emissions by 2050, intensifying climate change.

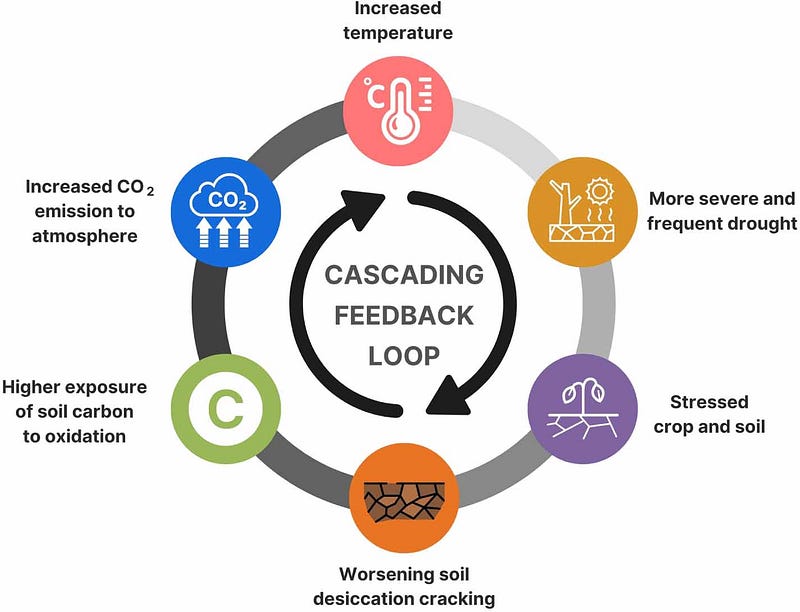

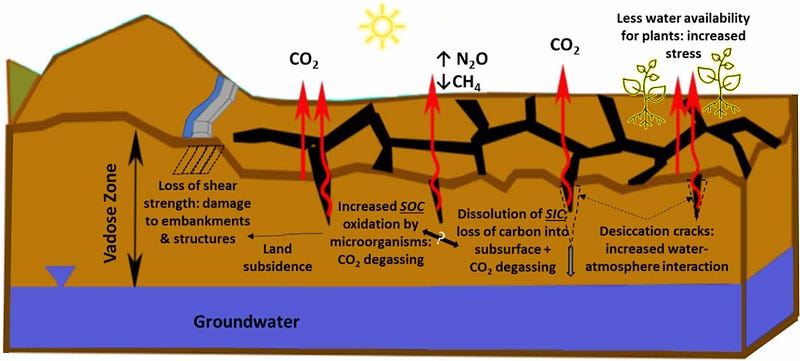

Research published in Environmental Research Letters indicates that persistent and severe droughts are causing these carbon-rich soils to crack and degrade, releasing more CO2 and other greenhouse gases. The repercussions extend beyond emissions; deteriorating soil health can diminish photosynthesis and CO2 absorption, compromising the stability of earthen dams that guard against floods.

The feedback loop involving drought, soil desiccation, and CO2 emissions remains largely ignored in many climate models. However, changes in soil due to drought could be as critical, if not more so, than other factors we typically consider. Drought-induced soil cracking exposes it to air, accelerating microbial activity and organic matter breakdown, which releases CO2 and reduces nutrient availability for plants. Additionally, deep cracks can unearth ancient carbon reserves that were previously stable and protected. When air reaches the soil, it not only hastens CO2 release but also increases emissions of other greenhouse gases such as nitrous oxide.

Even small soil organisms like earthworms and millipedes are adversely affected. The lack of moisture and increased air exposure hinder their roles in nutrient cycling and soil structure, further exacerbating soil degradation.

All of this is for the sake of feeding…cars and cows.

The Upside Down World: Cows and Cars Over Humans

Farmers and scientists are making progress in producing more food with less land. Yet, the focus often shifts away from the foods that humans actually consume. Each year, farmers gather in Houston for the National Corn Yield Contest, aiming to maximize corn production per square meter. In 2023, the champion, David Hula from Virginia, achieved an astounding 623.84 bushels of corn per acre, more than three times the national average.

Impressive, isn't it? This showcases the potential of agriculture when farmers effectively utilize available resources: high-quality seed varieties, optimal pesticide and herbicide combinations, precise fertilization, and timely irrigation. However, many farmers around the globe lack access to modern farming technologies, resulting in lower yields. The yield gap—the disparity between potential and actual crop yield—illustrates this issue. For instance, while the average corn yield in the U.S. is about 10.8 tons per hectare, Kenya's yield is only 1.5 tons, significantly below its potential.

Yield gaps highlight opportunities for increased productivity, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, a region facing severe hunger and a rapidly growing population projected to double by 2050. However, a significant yield gap is just as detrimental as no yield at all. As new crop varieties and farming techniques develop, the theoretical maximum yield tends to rise. But when it stagnates, it signals a lack of progress in enhancing crop varieties and farming practices. This is evident in rice, a staple that provides essential daily calories for a fifth of the world's population.

Conversely, crops like corn and soybean, which exhibit growing yield gaps, primarily serve as biofuels and animal feed rather than direct human consumption. This reality underscores the inefficiencies in our food production system, where farmland is squandered on non-essential uses, resulting in less food for people and reduced land available for rewilding. Enhancing agricultural productivity is essential for alleviating poverty, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, where a significant portion of the population lives in extreme poverty.

Meanwhile…

The world discards over 1 billion meals daily, even as hunger persists.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries represent only 16% of the global population yet account for 30% of organic waste. Overpopulation is often cited as the culprit, but the truth is, there is sufficient food for everyone. Food waste is a pervasive issue at every stage of the journey from farm to table.

Vegetables are discarded for being the wrong size, grains fall from conveyor belts, milk spoils during transport, fruits rot on display, and meat decays in packaging. Even leftovers end up in the trash. According to the UNEP's Food Waste Index Report 2024, 19% of global food production is wasted, with households being the worst offenders at 43%, followed by food services at 26% and retail at 13%.

Picture this: every seventh truck transporting fresh food is essentially a garbage truck. The same workers who stock the shelves also toss the products in the bin. The more we consume, the more we waste.

The World Food Programme (WFP) reports that in 2023, over 345 million people are facing severe food insecurity, with as many as 783 million experiencing hunger. Each year, hunger claims approximately 9 million lives, including 3.1 million children.

Here are some startling statistics: One-third of food produced globally is lost or wasted, equating to about 1.3 billion tons annually—worth approximately $1 trillion. This wasted food could nourish two billion people, more than double the number of those currently undernourished. The food waste from wealthier countries is nearly equal to the entire net food production of sub-Saharan Africa each year. In developing nations, 40% of losses occur during the post-harvest and processing stages.

However, food waste is not merely a social issue; it poses a significant environmental threat. Decomposing food in landfills generates methane, a greenhouse gas much more potent than CO2. In fact, food waste contributes to 8% of global emissions. If food waste were a country, it would rank as the third-largest CO2 emitter globally, following the USA and China.

Moreover, wasted food signifies wasted resources, time, and energy. Agriculture consumes 70% of the world's freshwater supply, meaning food waste significantly drains our water resources. Each year, the water used to produce uneaten food could fill Lake Geneva three times over. Discarding a kilogram of beef wastes around 25,000 liters of water used in its production. Throwing away a liter of milk equates to wasting over 1,000 liters of water.

Globally, an agricultural area larger than Qatar is used to cultivate food that ultimately ends up in the bin.

Taking Action Against Land Waste

It's a challenging dilemma. Should I feel more despondent or optimistic about our situation? In many ways, our global waste mirrors our needs. We live in a time when I can order shoes from a Chinese warehouse and receive them at my doorstep in Patagonia in just a few days. Yet, one in five meals produced goes to waste. We have self-driving cars and advanced technologies, but the underlying ethos remains the same: consume as many resources as possible and assume everything will be fine.

Land restoration does not occur overnight. Our waste leads to tragedy. While nearly a billion individuals go to sleep hungry every night, another billion knowingly discard enough food to nourish them. We are playing a precarious game, teetering on the edge of critical tipping points within our Earth's systems, all for food destined for the trash.

Investing in land restoration could provide solutions to multiple crises, not just land degradation. A report by the World Economic Forum suggests that dedicating approximately $2.7 trillion annually to ecosystem restoration, regenerative agriculture, and circular business models could create nearly 400 million new jobs and generate over $10 trillion in economic value annually. Comparatively, this is negligible next to the $11 million per minute the fossil fuel industry receives in subsidies. Disturbingly, for every dollar allocated to combat climate change, we spend at least five on subsidies that exacerbate the issue.

Nevertheless, governments worldwide continue to squander over $600 billion on direct agricultural subsidies, which could be redirected to support land restoration and yield-enhancing practices. It is irrational to use public funds to undermine our natural resources, yet this pattern persists election after election.

One reason land degradation has largely gone unnoticed is that many have lost their connection to it. As urban dwellers, we are distanced from food production. Furthermore, affluent countries have long dismissed the issue of land degradation as an "African problem." In reality, land degradation and drought affect nearly every nation.

With global food demand projected to rise by 50% by 2050 and climate change potentially reducing yields by 30%, the issue of land degradation cannot be ignored. Ultimately, we all bear the consequences. That half-eaten meal in the trash—what was the point of all the effort? Why did we plant, nurture, harvest, and transport? We labor tirelessly to keep the global supply chain functioning, only to discard 40% of our achievements. Each time food ends up in a landfill, we waste not just calories but lives. This stark reality illustrates how our relentless quest for more has left us feeling empty and drained, ensnared in a cycle of scarcity.

Now, let’s take a moment to reflect. Imagine if we had a choice.

Let’s ask ourselves: Is this truly how we want to live?

Be loud.

Thank you for your attentive reading and support!

Subscribe for immediate insights and join the 400+ Antarctic Sapiens community for weekly thought-provoking content.

Chapter 2: A Call to Action

The first video, "Seattle is Dying | A KOMO News Documentary," explores the social and environmental challenges facing the city, underscoring the need for urgent solutions.

The second video, "Michael Moore Presents: Planet of the Humans | A Film by Jeff Gibbs," critiques contemporary environmental movements and the impact of human activity on our planet, urging viewers to rethink our approach to sustainability.